Table of Contents

Click on a headline

to go to that story

Homer, the fictional character, embodies several American working class stereotypes: he is crude, overweight, incompetent, clumsy, lazy and ignorant; however, he is fiercely devoted to his family.

| ||||||

Creeker Chronicles

A compendium of anecdotes and stories by

Contributing Editor Ross Simpson

Ross Simpson: Eyewitness to History

As Told To Jim Sullins

For almost a half century, Fern Creek Class of 1960 alum Ross Simpson has chronicled events that shaped our world. The journey has taken him thousands of miles from home and filled three passports with hundreds of visa stamps.

One early dateline found Ross in a bitterly cold Distant Early Warning radar site, on St. Lawrence Island in the Bering Strait of Alaska. There, in October, 1962, during the Cuban missile crisis, a small, intense group of airmen scanned the Siberian skies for signs of a Soviet attack.

Forty-one years later, in March, 2003, as an embedded journalist, Ross reported the Iraq war, in the searing desert during Operation Iraqi Freedom. Between those historic events, Ross covered armed conflicts in Panama, the Persian Gulf, Somalia, and Haiti.

After his discharge from the United States Air Force in 1965, Ross began a 45-year broadcasting career in Washington, D.C. that included stints at three major radio stations, WTOP, WWDC and WRC, and career-enhancing stops at two radio networks, the Mutual Broadcasting System and The Associated Press Radio Network.

Along the way, he covered major events in this country and abroad, including the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King and the riots that followed in Washington, D.C.

When John Hinkley, Jr. attempted to assassinate President Ronald Reagan, Ross rushed to the hospital where the President was taken, gained access and was briefed by attending physicians on Reagan’s life-threatening wound.

Being a correspondent for a major news gathering organization like The Associated Press has given Ross access to people, places and things not available to most people. He has flown with the Navy’s Blue Angels and the Air Force Thunderbirds, and has logged “stick time” in nearly every fighter, bomber and helicopter in the U.S. inventory. He has flown supersonic in the F-14 Tomcat and F/A-18 Hornet, and has spent time on five aircraft carriers, in harm’s way. Ross was on board the USS Key West, a Los Angeles Class nuclear attack submarine that was playing cat and mouse with a Russian sub, deep in the Atlantic, the night former Russian President Boris Yeltsin came to power..

In between major assignments and anchoring almost 100,000 newscasts, Ross has authored four books, including a best seller on the Fires At Yellowstone in 1988 and hundreds of magazine articles about his adventures.

Approaching retirement, Ross is putting the finishing touches on his fifth book, an eyewitness account of what it’s like for a civilian to ride into battle with Weapons Company, 1st Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment, 1st Marine Division, from the Rumalyah Oil Fields in southern Iraq to Baghdad.

Mrs. Helen Collings, his English teacher at FCHS, once told Ross that he could be a writer if he worked at it.

Moments before embedded journalist Ross crossed the Iraq border in MOPP-4, in full chemical warfare gear in the backseat of his platoon leader's Humvee where he would sleep, eat and work during the war. What a handsome fellow!

Ross reporting. using a satellite phone. After 21 days in heavy combat, the Marine battalion he was with finally seized the al-Azimiyah Palace on the Tigris River in Baghdad, the final objective of the invasion of Iraq.

Ross at the National Museum of the Marine Corps, in front of the War Correspondent's exhibit that includes gear he wore in the Iraq war

Ross Simpson at Homer and Alice's graves in Mt. Washington, on a day when the crowd was light.

Homer and Alice Simpson, dad and mom to four Fern Creek kids. The family was nothing like the TV one.

Cartoon sketch of Homer Simpson TV fame. The love of a cold beer was the only thing the Real Homer Simpson had in common with his TV counterpart. The real Homer drank Sterling.

Associated Press Radio Anchorman Ross Simpson broadcasts from studios in Washington, D.C.

The Real Homer Simpson

by Ross Simpson, Contributing Editor

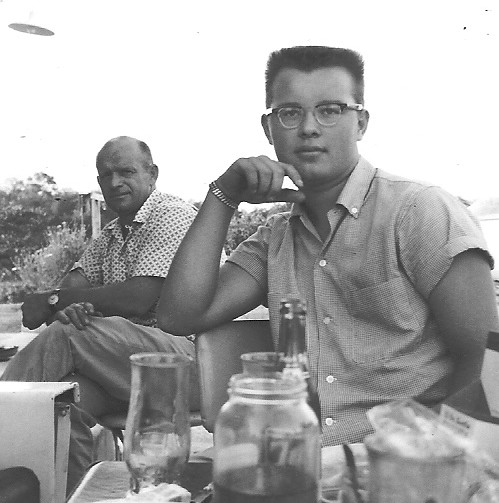

The real Homer Simpson with son, Ross.

On a recent visit to Fern Creek, Ross visited the old family home place and found Homer's black wall phone still hanging on the basement stud, with the original family phone number intact.

After changing his phone number, Homer's other woes included stolen mailboxes and uninvited televison reporters