The Editor

Tales, Comments and Observations

By Jim Sullins

TigerGazette.com

Faline and McDuff eventually made friends. She kept him company as he made his daily rounds, providing "security" to our little farm.

Deer Lives In House, Loves Dogs, Survives Gunshot Wound

Jim Sullins

Happy Editor

Unhappy Editor

Not the subject of our story, but the Rosenberry General Store still operates in Donnelly, Idaho, after more than one hundred years.

'Can Do' Store Clerk Uses Old Fashioned Method to Save the Day in Donnelly, Idaho

At a time when twin engine airliners were the norm at Standiford Field, flying on an Eastern Airlines Constellation was a big deal.

THE SET UP

Washington National Airport, located in Arlington, Virginia as it appeared in 1960. The soaring height of the main terminal's interior spaces, decorated with aviation, murals is what consumed a young boy's attention.

This was more than an ‘oops’ moment, because I envisioned the Newark-bound plane rolling down the runway sans one distraught kid.

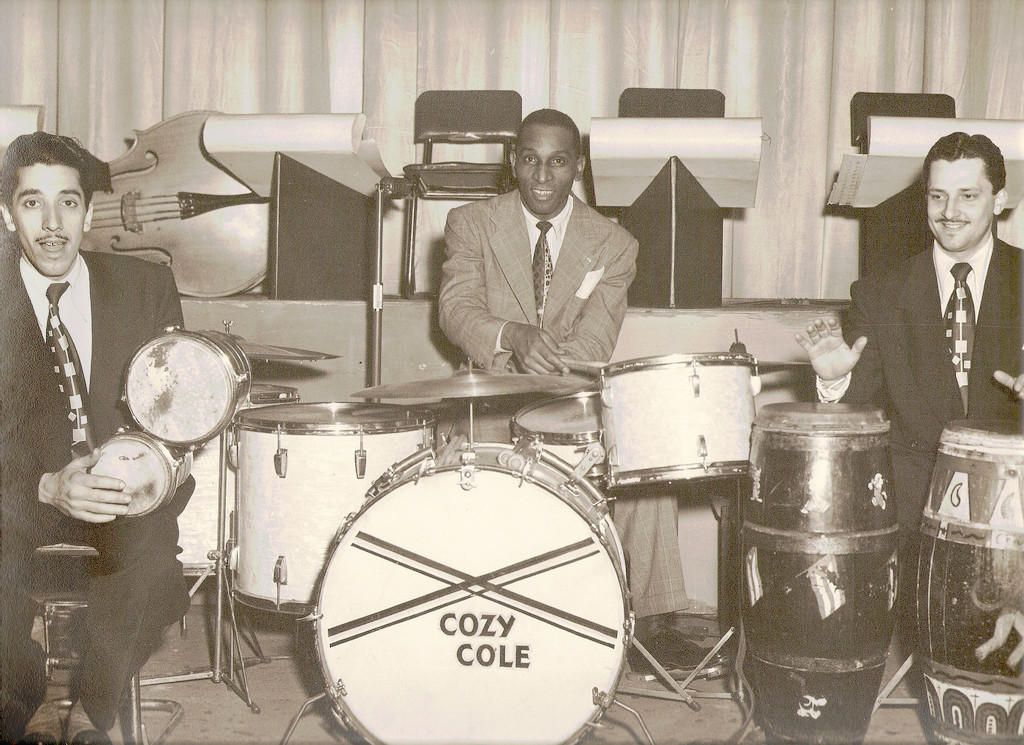

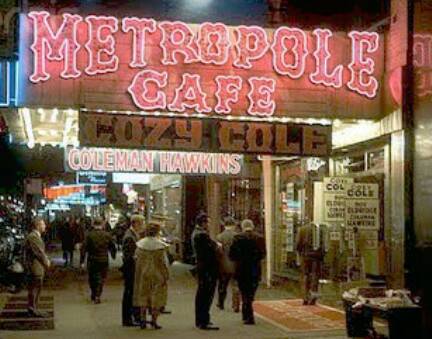

Cozy Cole appeared at the Metropole Cafe for years, after making a name for himself with jazz greats like Cab Calloway and Louis Armstrong.

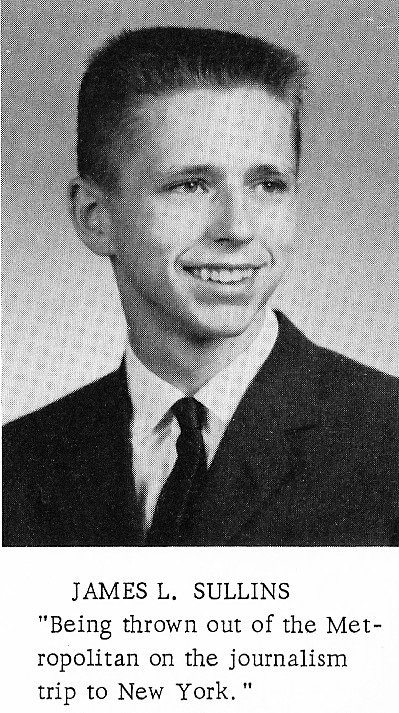

Wearing the same clothes as during his NYC adventure, our protagonist posed for his senior picture, below which appears the error that sealed his fate forever.

THE PAYOFF

For Tiger Gazette Sports Editor, There Was No Jazz In New York City

The Metropole Cafe, famous New York Jazz Club near Times Square, featured big names in jazz, including Lionel Hampton, DIzzy Gillespie and, above, Cozy Cole and Coleman Hawkins, better known to jazz aficionados.